The Meme Studies Research Network (MSRN) Index is a collaborative project that collects and presents academic literature about the use, spread and impact of internet memes. The MSRN index was modeled after the Cyberfeminism Index facilitated by Mindy Seu and LSE Digital Ethnography Collective’s reading list. You can visit it on memestudiesindex.com.

Internet memes increasingly help steer politics, culture, sociality and consumption in contemporary society. They are cheap and easy to make, disseminate and monetise. As forms of civic expression they hold symbolic and material power within global digital cultures, and can quickly spread from online platforms into seemingly offline spheres. We make sense of the everyday as well as the extraordinary through internet memes, interpreting public events and personal crises via memetic templates and ironic communion online.

Meme creation can be euphoric, almost libidinal. Meme creators will often tell you the best memes are those that are made in a split second, those ones that they don’t labor over for hours. This euphoria can extend to the comments section of an Instagram meme or a TikTok post, and infect the audience. A temporary sense of community can be found in the comments, where people riff off each other’s jokes, and create a makeshift, impermanent space for momentary meme-induced catharsis.

At the same time, this libidinal pull of meme creation and dissemination unsurprisingly informs a lot of the antagonistic subcultures of the internet. Memes are used to harm, bully, troll and threaten just as they are used for laughter, critique, resistance and communion.

The ubiquitous nature of internet memes, as well as their manifold functions make them a vital part of contemporary social life. However, they are slippery and evade definite categorisation, they morph and shapeshift from one day to the next - by the time you can recognise one iteration of a meme, it has already been remixed and deepfried by a thousand people, on a thousand different platforms.

So how do we catch the cunning, mercurial meme and take a good look at it? Can a meme ever be a subject of scholarly examination? What would happen if I put the meme in a beaker and mixed it with some hydrochloric acid? Would I need to wear safety goggles?

Thankfully, there are people who have already done this (no need for Bunsen burners). Scholars have written and published academic works about internet memes and their roles in society since the early 2000s. You can find academic articles about everything from 9/11 jokes (Kuipers 2005), to the Harlem Shake (Soha and McDowell 2016) and the affective labor that meme creators on Instagram engage in (Holowka 2018) within this literature.

The only problem is that they are often difficult to find for people who are not already embedded within academic spaces. At university, you may be taught how to do an academic literature search in order to find scientific, peer-reviewed sources, by taking a “research methods” class. So, looking for trustworthy academic research online is a skill that can be learned and taught, but can be inaccessible to those outside of the Ivory Tower.

When I first started my PhD in 2018, even equipped with the research skills I mentioned above, I found it difficult to access up-to-date meme research. I felt that there was a limited amount of resources available and I had already read all of them (I hadn’t). Trying to google something like “articles about internet memes” would result in a flurry of non-academic results, buried under KnowYourMeme entries and journalistic pieces, which was not what I was looking for. An ideal place to start for me would have been a meme studies reading list that I could consult for an initial entry into the literature. I couldn’t find such a list, so I gave up and started to build my own library on an academic citation software called Zotero. By early 2020, I had a growing list of academic articles about internet memes that I was citing in my PhD research, covering topics such as identity, feminism, art, and politics.

But by November 2020, I was stuck in a damp and dark apartment with no access to an office, library, or intellectual camaraderie. As a result of the pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns, the academic communities and networks that I relied on for support were out of reach. The only connection I retained to the academy was through my digital devices. Feeling lonely and understimulated I started using social media, and in particular, Twitter, more actively.

Thanks to the scholars I followed on Twitter, I was exposed to different and inspiring modes of academic research and knowledge exchange that I didn’t know existed before. I had been following the LSE Digital Ethnography Collective on Twitter for a while and had made use of their digital ethnography reading list for my own research previously. I was inspired by the co-founders of the collective (Zoe Glatt and Dr Branwen Spector) and how they used their academic credentials to make knowledge about online research more accessible. They had made an open-access reading list for academic resources on digital ethnography, and would post the seminars they hosted at LSE about topics such as online research methods, digital platforms, and digital culture on YouTube.

At the same time, I saw people tweeting about something called the Cyberfeminism Index. My ears perked up at the mention of cyberfeminism. I found out that it was an “in-progress online collection of resources for techno-critical works from 1990–2020 facilitated by Mindy Seu ‘’ and commissioned by Rhizome. Coming across this exciting project was serendipitous, as I was trying to understand the connections between the internet, feminism, digital technologies, resistance, community, and capitalism to better contextualise my own PhD work, which focuses on the labour that goes into the making and sharing of internet memes.

I would go on the index (www.cyberfeminismindex.com) and find captivating texts and weird websites that I otherwise would not have come across. It was an amazing experience - after years of using google as a portal into information, I had unknowingly internalized this motto: “if it’s not on google, it doesn’t exist”. The thematic curation of the Cyberfeminism Index was so exciting in comparison to my daily digital experience. I felt like I could bypass google’s algorithmic control of knowledge, and instead lose myself in this index, like I would in a library. It was soothing, meditative, fun, informative.

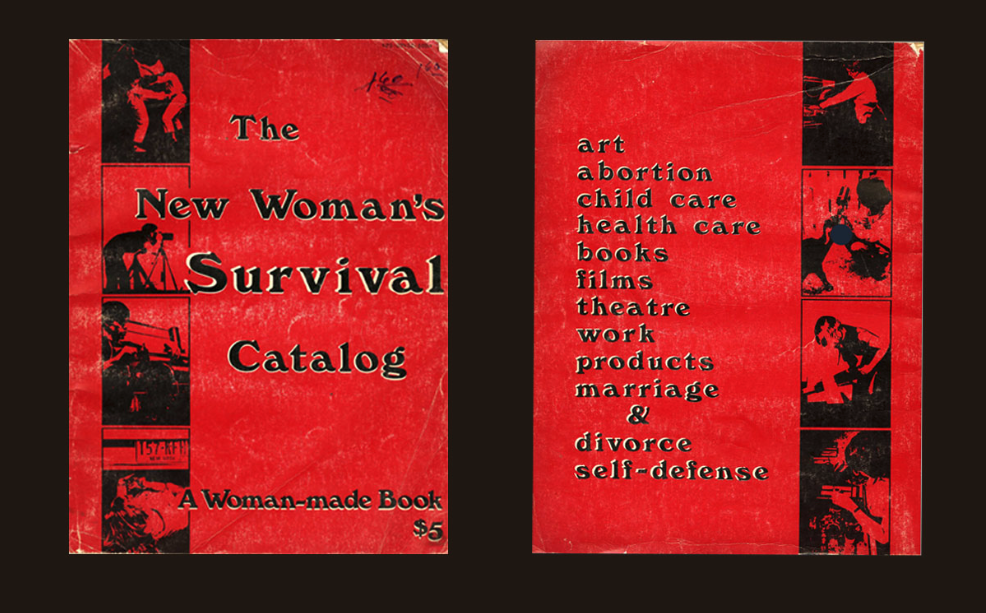

In an interview about the Cyberfeminism Index, Mindy Seu mentions how she was inspired by the idea of “sharing as survival” that underpin feminist resource guides, such as the The New Woman’s Survival Catalog (billed as the “pre-internet feminist internet”). These feminist guides were pulling resources together and presenting them for people who may not be able to access each source separately.

In this interview, Seu also underlines the “politics of citation” in knowledge creation and exchange, and states “we cite as a way to ‘legitimize’ certain practices”. Citation is vital in how we understand what kinds of knowledge is trustworthy, legitimate, scientific, robust, and valuable, and should therefore be taken seriously. By citing certain people over and over again, we also run the risk of making other people’s work invisible.

This doesn’t have to be maliciously intended, it can be that we haven’t had the time to look beyond what has already been cited and vetted, and we may even be burnt out and intimidated by the overabundance of information we have access to due to the ubiquity of digital technologies. This was how I felt when I first started my PhD journey, afraid of the vastness of the knowledge that I couldn’t possibly parse over 4 years, and at the same time, restricted by what google could offer me.

Going back to November 2020, after witnessing the creative ways that knowledge could be shared online, I decided that I would make the library I had started on Zotero available online to anyone who may be interested in studying internet memes. My feeling was that, if I was having difficulties finding and collecting research about internet memes, so were other scholars. The pandemic had made it challenging for me to feel like I was a part of a research community, and by sharing this library I thought I’d be able to connect with others who were also studying digital culture, specifically internet memes. So after I converted the Zotero library into a PDF and put it on google docs, I sent out a tweet asking if anyone would be interested in co-editing and developing this document with me. I got a lot of positive responses, and lots of DMs. People had been looking for something like this!

I quickly realized that there were many people who were excited by the possibility of forming a meme studies community. This is when I messaged Zoe Glatt, from the LSE Digital Ethnography Collective, and explained that I was thinking of setting up a collective similar to theirs. I asked for her advice on how to facilitate such an endeavor, and she gave me a roadmap to ways of bringing people together online. This was extremely useful, and I felt grateful that instead of gatekeeping this knowledge, Zoe was more than happy to share her wisdom with me. A discord server, a mailing list, and a Twitter account later, the Meme Studies Research Network (MSRN) was born, thanks to all of the support from scholars such as Zoe, as well as contributors and members such as Madeleine Hunter, Giula Giorgi, Hester Hockin-Boyers, Lucie Chateu, Danielle Rudnicka-Lavoie, Natalia Stanusch, Dr Liam Mcloughlin, Cem A., and many others.

Today we have over 400 people on our Discord server, our “Meme Studies Reading List” (the Zotero library turned google doc) has been mentioned in various newsletters and podcasts. People have made use of it to write journal articles, essays, blog posts, and dissertations. However, our long term goal with this reading list was to turn into its own index so it could be accessed as a stand-alone website.

I was inspired by the Cyberfeminism Index, its content and curation, as well as its minimalistic design. I had discussions about turning the list into an index with Nik Slackman from Bard Meme Lab, who suggested that we start a google sheets file and start cataloging all the sources in preparation. I then broached this topic with Jillian and Omnia from virtualgoodsdealer and they were very interested in building something together.

This was an exciting opportunity, as I had interviewed both Jillian and Omnia for my PhD and was writing about virtualgoodsdealer as a creative, entrepreneurial intervention that seeks to circumvent platform-dependency. So the chance to work with them on building new avenues for knowledge creation, fit well into virtualgoodsdealer’s ethos as well as my research principles.

I managed to secure a small funding award from Edinburgh Future Institute’s student research project scheme, and we got to working. Jillian started building the website, and Omnia and I continued cataloging the sources on the google sheets file. After several months of collaboration, facilitated mainly by a Discord group chat, the index is ready.

On the Meme Studies Index you can find a selection of academic, and academic-adjacent, articles and essays on the use, spread, and impact of internet memes.

We have included some thematic tags, which will show you the topics, platforms and places that the resource in question addresses, visible on the right hand side. If you click a tag, you will be taken to a page where you can see other sources that have been tagged with the same topic.

As Mindy Seu says about the Cyberfeminism Index, the Meme Studies Index is also “INCOMPLETE and ALWAYS IN PROGRESS”.

The index should be taken as a guiding resource, but not as a definitive catalog of all academic research about internet memes. The way we compiled this index was subjective, and done on a more-or-less voluntary basis, which makes it limited in ways that it wouldn’t be if it were funded on a larger scale. We are always looking to expand it and if you have suggestions of sources that you think we should add to the index, please email memestudiesrn@gmail.com. We will update the index whenever we are able to do so, but rest assured that this will be an ongoing and living project.

Thanks to all the members of the Meme Studies Research Network who contributed to this project, and to Emma Damiani who worked with us to create the new MSRN and MSRN Index logo, which we will be using from now on.

I hope that you find the Meme Studies Index useful!

This article was adapted from a blog post originally written for The Meme Studies Research Network blog. The Meme Studies Research Network Index is also featured in virtualgoodsdealer pages exhibits.