Will they take over the world? More importantly, will they put me out of a job?

Over the years, as a child who built solar-powered boats and robot arms from science kits, then as a team captain of my high school FIRST Robotics competition, as an undergraduate majoring in a Mechanical Engineering with Robotics flex degree, as an MIT Media Lab research assistant on a big (seriously, big) robotic construction platform, and finally working on DARPA robotics research and robotic applications in industry….

I have received many, many questions about robots.

Hopefully, this litany has outlined why I am qualified to explain this topic, the last qualification being, I can also write and explain things pretty well for an engineer, if I do say so myself. Some caveats:

- I am young, and relatively early in my career. I don’t have a PhD and I am not the head of a robotics company. But the field is pretty young, too. You might have reason to be suspicious of what some of those more established people might have to say — maybe they have an incentive to put a particular spin on robots, if they run a company that builds them or if robots are their life’s work. I don’t have as much of an incentive; I can still leave this field and pursue a medical device career or something (but I do love robots).

- This post will contain several Hot Takes (TM). Just roll with me ‘til the end and have fun, I don’t pretend it’s all perfect or that I know everything — that’s why I call them ‘hot takes’ and not ‘immutable truths’. I’d be more than happy to further engage and debate about the definitions and implications of technology!

Why are you writing this blog post?

Though there are many articles on this subject (and I encourage you to read them) in my opinion, few people have done a good job explaining what robotics and automation means for you. Few people explain the technical stuff, the research stuff, and the implications for business and government and so on. People want to know what’s really going on right now, and most people are going off of viral, creepy Boston Dynamics videos, which look cool but don’t explain much about how robots actually work.

Hence, why people keep asking me questions.

The Central Question: Are you gonna put me out of a job?

All the questions that I’ve ever received seem to revolve around this one. I will address this incredibly common question in two parts. The first is social in nature, the second is technical and practical.

Social Implications of Robots

Let’s look at one very big field in robotics right now: e-commerce.

The bulk of automation in e-commerce and manufacturing is actually motivated by the fact that there are not enough people.

Let me say that again. There are not enough workers, so automation rushes in to fill the gaps.

Now, I’m not going to just give giant corporations a free pass here. Part of the reason there are not enough people are because wages are low, benefits are meh, and the jobs are very tedious. Growth-track employment opportunities are dwindling in favor of the “independent contractor” model. There’s no promise that a job in order fulfillment will ever be more than just a job. The companies around these positions have a major role to play in making these positions undesirable.

That said, at the end of the day, even if there is great pay and benefits, running around a warehouse all day is rarely going to be desirable. Autonomous ground vehicles, championed by Kiva Systems (now Amazon Robotics) made this job less tedious and labor intensive, by using robotic vehicles to bring the goods to the person (this is called “goods-to-person”) instead of sending people around the warehouse to find the goods.

My point is more so that the relationship between technology and jobs is complex, and society and government have a major role to play in managing that relationship. Once again, corporations and makers of technology don’t get a free pass, but the ethics are not as straightforward as, say, renewable energy (“good”) or weapons design (“bad”). I think we should generally allow for the development of technology so that people can have the advantage of its benefits. The question of which people capture those benefits is a much bigger question about capitalism, regulation, and government.

There is a world with robots that makes the rich richer and the poor poorer. There is also a world without robots that makes the rich richer and the poor poorer. Depending on the robot, the ‘bot itself might replace workers entirely, in which case the technology pretty directly destroys some jobs, or it might simply make people more efficient (as in the case of goods-to-person). But the bigger societal question is the one I see as more important. It’s not always technology itself that eliminates certain jobs, exactly, but broader trends — what is responsible for the disappearance of telemarketers? We still have, and use, phones.

I offer Hot Take #1: Technology just accelerates existing trends, whatever the trends are. In some cases, the technology is underfunded, or regulated to the point of being impractical. In other cases, money is poured into a certain innovation, red tape is cut away, and it flourishes. How those financial and regulatory forces should approach robots as they improve, I leave an open-ended question — maybe some kind of ‘robot tax’, or something else to motivate giving humans better positions and work environments, which is what we really want.

What is the state of robotics right now?

I offer you this video, “Autonomously folding a pile of 5 previously unseen towels”.

This video is at 50x speed…which means it takes the robot something like 20 minutes per towel. Granted, this is 9 years ago and it is pretty impressive that the towels are “never-before-seen”.

This, too, is a lovely gem (the things that fancy universities and companies don’t show you…)

This is where robotics is right now — there are a lot of heated debates about AI and ML, but in terms of robots interacting with their physical environment, there is a long, long way to go. (Each of those falls in the second video can be very expensive, by the way).

Hot Take #2: Every AI company is an ML company.

What’s the difference between AI (Artificial Intelligence) and ML (Machine Learning)? One joking answer is, “if it’s written in [the software language] Python, it’s ML, if it’s written in PowerPoint, it’s AI.”

The point of the joke is that the field of AI asks big, broad questions, like what is intelligence? What does it mean to be human and have human intelligence? Is intelligence actually something that’s part of human identity, or is it really empathy? How do people learn and how can we make learning machines? Is intelligence as humans understand it biased — is it a logical fallacy that we think the dolphins are dumber than us? (The dolphins didn’t mess up the earth with climate change, after all) Can we really understand our own intelligence, or would it require something more intelligent than us to understand ourselves? What about definitions — what should we define as intelligence? If we make a definition that is too narrow, your calculator is artificial intelligence; if too broad, it’s hard to classify the ‘progress’ we make toward AI.

AI touches on computer science, design, neuroscience, even philosophy in a way. ML, on the other hand, is a specific category of software algorithms; a category of numerical methods and mathematical approaches. These types of algorithms have to look at 50,000 images of chairs to understand what a chair is. A human baby needs to only see about the number of chairs in its household. The baby, as it grows, can identify weird chairs too, sculptural chairs, art museum chairs that the ML algorithm might fail to “see”.

AI asks the question, why is a baby so much better than an algorithm? Maybe we’re being unfair to the algorithm. Maybe the baby developed this understanding through evolution, or something, so really somewhere deep in its DNA is the memory of thousands of chairs seen by its ancestors. Sounds crazy, right? But this is a real theory. For ML companies to call themselves ‘AI’ is, to me, extreme arrogance. We have not actually decided whether ML qualifies as AI or not. In the neighboring field of neuroscience, we still don’t understand how our own brain works.

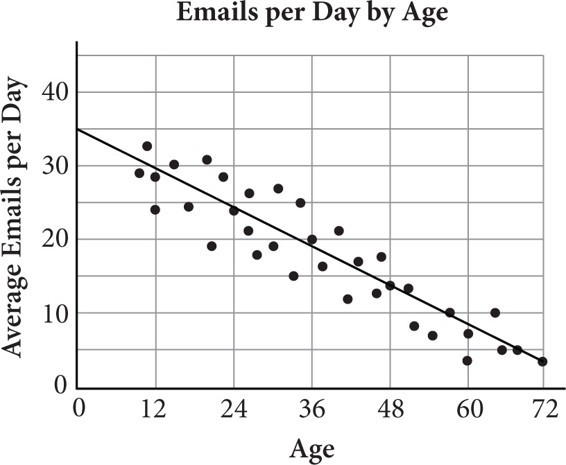

And ML is just big data. Yeah yeah, it’s complicated and whatever (I told you there would be a lot of hot takes). But at the end of the day, ML is what you did in high school science or math, when you looked at a plot of data you collected and drew a line of best fit.

A quick refresher for some of you — this idea is that we can plot real-life data (which is messy and doesn’t fit on a precise line) and then make a line that we can use to help us make predictions, or make the information easier to understand. For example, data on housing prices with a line that has a very sharp upward slope can tell us that housing prices are increasing very quickly. Similarly, if it’s a curve that is fit to real-life data and changing over time (most of you are familiar with this in the age of COVID-19) as the curve gets flatter or steeper, we know that the situation is changing more or less rapidly and it informs our decisions.

That’s ML.

Instead of a line or curve, we have even fancier graphs now. We even have weird multi-dimensional data representations so we can do funky math things with the data. But at its core? That’s all it is. That’s why it needs to see 50,000 chairs, because the thing-of-best-fit needs to be really, really good.

A huge, important point here is that ML still relies on human intelligence!!! How do you think the algorithm gets trained on 50,000 labeled images of chairs? Human beings label those images so that during the “training” period, the ML can say “I think this is a chair” and then check the label of the image to determine the truth. The proliferation of ML companies has created work for human beings to label training data, work that is often low-paying and outsourced to the global south.

A.I. Is Learning From Humans, Many Humans.

Yes, after being ‘trained’ the algorithm can run off and perform independent, new tasks impressively, to the point of being called AI, but the core of any ML algorithm is the data it was trained on.

This data can be biased, and that bias has severe implications, as pointed out in ongoing discussions by Data for Black Lives and the Algorithmic Justice League around facial recognition technology. To put it plainly, if your training data is 50,000 images of white men, your ML facial recognition algorithm will not be able to accurately recognize the faces of women and people of color.

To be clear, ML is still very powerful. It’s hard to process tons of data, and we had to come up with fancier math and more powerful computers, and there’s a reason this technology has reached its zenith only now. ML still keeps me up at night — but my nightmares are probably different than the Silicon Valley VC’s and startup engineers. The use of ML in facial recognition, determining credit scores, and other applications has been shown to be inaccurate at best and racist/discriminatory at worst. These issues— issues rooted in the people, the designers of the algorithms and tools, the biased data which algorithms are trained on — are what bothers me, not the idea that ML will someday get so good it becomes self-aware and takes over humans.

What if intelligence is also somewhat physical?

All of this said, ML is still pretty powerful which is why some (ok, most) choose to call it a form of AI. Algorithms that can perform high-level analysis are indeed impressive. Look at this crazy, incredible shit:

Let’s go back to what we deem as the best example of intelligence, a human being. We have many sensors to interact with our world, and we gain and compile information at incredibly fast speeds. On the software side, there’s the question of how our brains work to synthesize all this information. But doesn’t hardware matter too? How can we understand anything if we cannot see and interact with the world right in front of us?

I could go on and on about this subject, since this is the area of robotics that I am most excited about and have positioned myself in. A grad student I worked with at the MIT Media Lab once said, “who has better respect for nature — the roboticist or the biologist? I think maybe the roboticist.”

You don’t appreciate how efficient nature is until you start trying to copy it. Professor Hugh Herr, also at the Media Lab, is known for talking about how quiet muscles are — the motors in his prostheses whirr and click constantly, unlike the silent movement of mammalian muscles. Before we understand something as complex as the brain, we don’t even fully understand how muscles work.

Robots do not understand the ‘rules’ of the real world, and they sure as hell don’t have sensors as sensitive as dog’s noses or human eyesight. Robots do not understand physics. Robots do not understand that to pick up a cup, you should grab it around the center rather than an impossible point on the edge of the rim. You have to teach that to the robot, and someone’s PhD thesis at MIT was dedicated to just that problem (this field is called ‘manipulation’ and that problem is ‘grasping’) . The sensors of the robot, the physical structure of the robot — does that not also at least influence its intelligence? It is very hard to compete with nature on that front. There are also theories about human learning being embodied in way — your intelligence is not just in your brain, it’s also in the thousands of nerves all around your body, and some of our learning is impossible without our physical bodies. There are many of these expanded views of intelligence that I find so interesting.

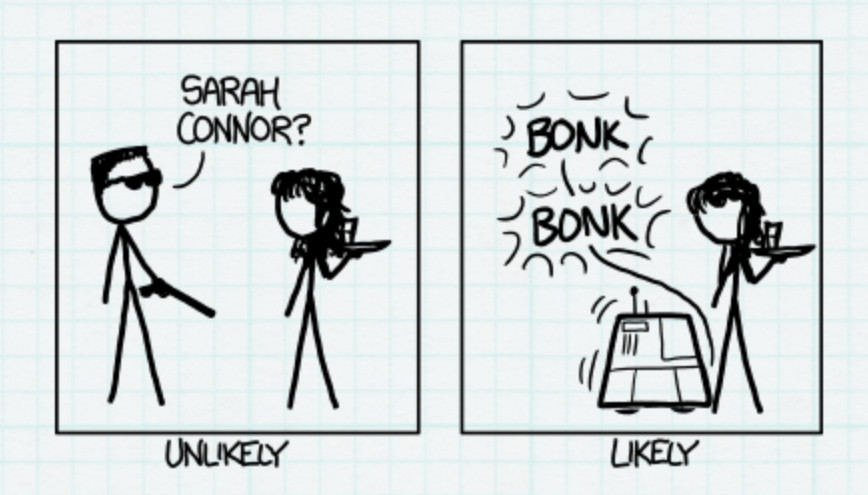

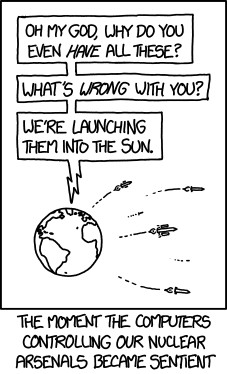

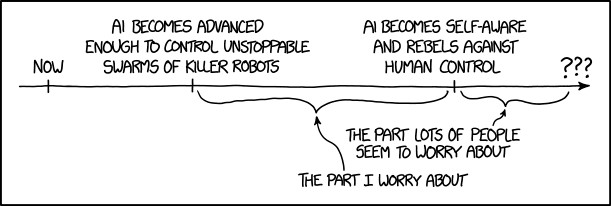

This is not a declaration that we will never get to true ‘artificial intelligence’, but it is a declaration that right now, we still have a long, long way to go, and there are so many uncertainties along the way. For those worried that reaching true AI would lead to some kind of malevolent AI, well, malevolence is also one of those uncertainties.

I feel that some of the hot shots in this field, especially in industry and Silicon Valley, don’t quite understand that. Here’s Hot Take #3: I feel we should focus more on the implications of these new and powerful technologies that are very real right now, like privacy and facial recognition as I mentioned, rather than worrying about an abstract malevolent AI future. Maybe we should even worry about how “Internet of Things” could lead to a Die Hard III-type scenario.

But a robot takeover? I see this as somewhat similar to worrying about the day the sun explodes, when the threat of climate change is right in front of us. It’s humans using powerful technology for bad things that concerns me first, not the technology becoming independent.

Appendix

I had a lot of fun writing this and I hope you had fun reading it! Here are some fun articles, comics, and resources:

- AI is Learning from Humans from NY Times

- Data for Black Lives

- “Forget about AI, Extended Intelligence is the Future” by Joi Ito from Wired

- “What if: Robot Takeover” from xkcd.com

It is my belief we can appreciate non-problematic works by problematic individuals (to an extent) as long as we acknowledge the problems and participate in criticism. While I appreciate this particular article, I recognize Joi Ito’s complicity in facilitating donations by Jeffrey Epstein to MIT, and his association to Epstein when formerly at MIT.